ENSURE HEALTHY LIVES AND PROMOTE WELL-BEING FOR ALL AT ALL AGES

- Introduction

- Global and National Targets

- Gap Analyses

- Human Rights Based Approach for National Targets

- UN Roles

Health and Human Rights

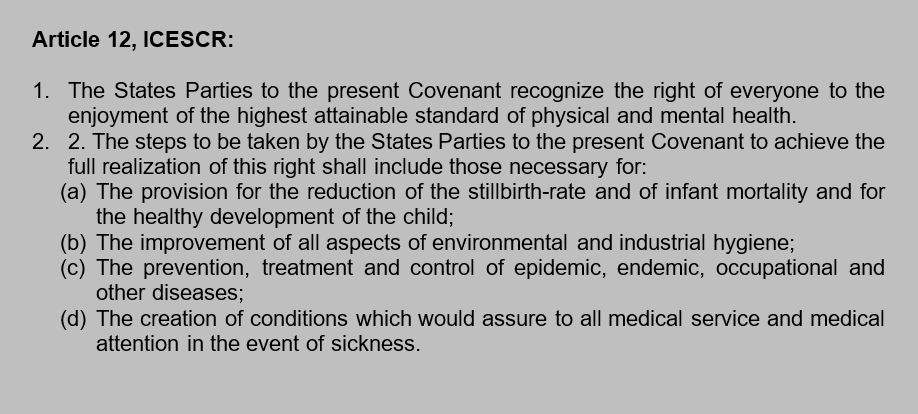

Health is fundamental for every human being to live to his/her full potential. It is indispensable to human life that it is recognized as a basic human right. The right to health is enshrined in the Universal Declaration on Human Rights, Article 25 paragraph (1) and in the ICESR, Article 12.

The right to health is also recognized in the 1945 Constitution, Article 28H paragraph (1), providing that “Every person shall have the right to live in physical and spiritual prosperity, to have a home and to enjoy a good and healthy environment, and shall have the right to obtain medical care.” The right to health is also recognized in the Law No. 36/2009 on Health, Article 4, providing that “Everyone has the right to health.”

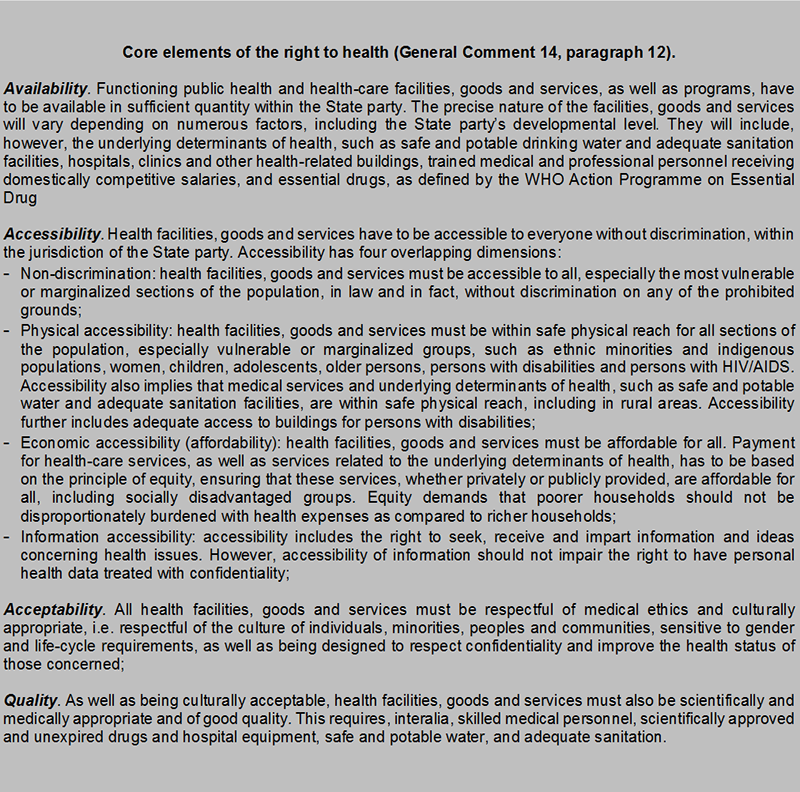

To provide a deeper understanding about the provision on the right to health in the ICESR, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) issue the General Comment No. 14 on The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health.[1] According to the CESCR, the right to health does not only include timely and appropriate health care but also to the underlying determinants of health, such as “access to safe and potable water, adequate sanitation, an adequate supply of safe food, nutrition and housing, healthy occupational and environmental conditions, and access to health-related education and information, including on sexual and reproductive health.” [2]

Furthermore, although the implementation of the right to health depends on the capacity and resources of each State party, it should, at least, include some basic elements namely availability, accessibility, acceptability and quality.

Indonesia has been implementing a universal healthcare coverage system since 2014 and by March 2016, the national health insurance program (BPJS) has been participated by more than 163 million people, with 63% are premium-subsidized participants.[3] In 2016, the GoI has allocated 5% health budget from the national expenditure budget.[4] However, the availability of quality healthcare facilities and healthcare personnel is still insufficient, hampering many people from the full enjoyment of their right to health, particularly for those who are poor and living in remote areas.

Currently, there are 1725 general hospitals and 503 special hospitals, mostly children’s and maternal hospitals, operating in 34 provinces in Indonesia, with hospital beds proportion of 1.12 per 1000 population.[5] Furthermore, there are only 9,908, out of 81,626 villages/kelurahan that have community health centers (Puskesmas), spread unequally between provinces, with the highest number in West Java (1.074 health centers) and the lowest is in North Kalimantan (50 health centers).[6] Indonesia is also lagging behind the WHO average of 2.28 doctors and nurses per 1000 population, with only 0.2 physicians and 1.4 nurses/midwives per 1000 population.[7]

In the latest report published by WHO in 2014, Indonesia shows that 75.3% of total health expenditure coming from out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditure, meaning that the majority of households were unprotected from financial hardship to access health services. The OOP percentage was even higher than the average of Southeast Asian countries average total health expenditure, which was 40.8%.[8]

[1] CESCR, General Comment No. 34 The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health, E/C.12/2000/4, 2000, available at: http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Women/WRGS/Health/GC14.pdf

[2] CESCR, General Comment No. 34, paragraph 11.

[3] BPJS, Jumlah Total Peserta BPJS Maret 2016, available at: http://infobpjs.net/jumlah-total-peserta-bpjs-maret-2016/

[4] Ministry of Finance, Informasi APBN 2016, page: 18, available at: http://www.kemenkeu.go.id/sites/default/files/bibfinal.pdf

[5] Ministry of Health, Indonesia Health Profile 2013, page: 35, available at: http://www.depkes.go.id/resources/download/pusdatin/profil-kesehatan-indonesia/Indonesia%20Health%20Profile%202013%20-%20v2%20untuk%20web.pdf

[6] BPS, Jumlah Desa/Kelurahan Yang Memiliki Sarana Kesehatan Menurut Provinsi, 2014, available at: https://www.bps.go.id/linkTableDinamis/view/id/935

[8] WHO, World Health Statistic 2016: Monitoring Health for the SDGs, page 17, available at: http://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2016/en/

| Global Targets | National Targets | National Indicators |

| 3.1 By 2030, reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100,000 live births. | 1. Increased health status of women and children;

2. Increased access and quality of healthcare for women and reproduction; |

a. Decreased number of maternal mortality to 250 per 100 thousand of childbirths by 2019 (2015: 306);

b. Increased percentage of births delivered in healthcare facilities to 85% by 2019 (2015: 75%); c. Increased percentage of births attended by skilled healthcare personnel to 95% (2015: 91,51%). |

| 3.2 By 2030, end preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5 years of age, with all countries aiming to reduce neonatal mortality to at least as low as 12 per 1,000 live births and under-5 mortality to at least as low as 25 per 1,000 live births. | 1. Increased health status of women and children; | a. Decreased mortality rate to 24 per 1000 births by 2019 (2012: 32);

b. Decreased neonatal mortality rate to 14 per 1000 births by 2019 (2012: 19); c. Increased percentage of neonatal first visit (KN1) to 90% by 2019 (2015: 75%); d. Increased percentage of comprehensive basic immunization for infants in regencies/municipalities to 80% to 95% by 2019 (2015: 71,2%). |

| 3.3 By 2030, end the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and neglected tropical diseases and combat hepatitis, water-borne diseases and other communicable diseases. | 1. Increased control over communicable and non-communicable diseases and increased environmental health; | a. Decreased prevalence of HIV to <0,5% by 2019 (2014: 0,46%);

b. Decreased prevalence of Tuberculosis (TB) to 245 per 100.000 of population by 2019 (2013: 297); c. Increased number of regencies/municipalities with malaria elimination to 300 by 2019 (2013: 200); d. Increased prevalence of regencies/municipalities to implement early detection on Hepatitis B for risk groups to 80% by 2019 (2013: 2,5%); e. Increased number of provinces with leprosy elimination to 34 provinces by 2019 (2013:20); f. Increased number of regencies/municipalities with filariasis to 35 by 2019. |

| 3.4 By 2030, reduce by one third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention and treatment and promote mental health and well-being. | 1. Increased control over communicable and non-communicable diseases and increased environmental health;

2. Increased quality of and access to mental health and drugs rehab facilities. |

a. Decreased percentage of smoking among population ≤18 years of age to 5.4% (2015:7.2%);

b. Decreased prevalence of hypertension to 24.3% by 2019 (2015:25.8 %); c. Non-increase prevalence of obesity among population above 18 years of age to 15.5% by 2019 (2013: 15.4%); d. Percentage of women between the age of 40-50 years to have early detection of cervical and breast cancers; e. Increased number of regencies/municipalities to have community healthcare facilities (Puskesmas) providing mental healthcare services to 280 by 2019 (2014: 50); f. Increased percentage of regional general hospital to provide mental health/psychiatric services to 60% by 2019 (2014: 13.5%); g. Increased proportion of treatment for households with mentally-ill member(s) to 61.8% by 2019 (2014: 38.2%). |

| 3.5 Strengthen the prevention and treatment of substance abuse, including narcotic drug abuse and harmful use of alcohol. | 1. Increased provision of social rehabilitation for substance abuse victims.

2. Increased implementation of the Prevention and Eradication of Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking (P4GN); |

a. Increased number of substance abuse victims to receive social rehabilitation in standardized service facilities to 210 by 2019 (2015: 200) and outside facilities to 4,319 by 2019 2015: 1.464);

b. Increased number of developed/facilitated Social Rehabilitation Facilities for Drugs Victims to 85 by 2019 (2015: 75);

c. Increased number of active volunteers to conduct preventive measures against drugs abuse to 5.302 by 2019 (2015:1.732); d. Increased percentage of healthcare facilities to provide service for active substance abusers with compulsory reporting obligation. |

| 3.6 By 2020, halve the number of global deaths and injuries from road traffic accidents. | a. Decreased ratio of traffic road fatalities to 11.22% by 2019. | |

| 3.7 By 2030, ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health-care services, including for family planning, information and education, and the integration of reproductive health into national strategies and programmes. | 1. Increased prevalence of contraceptive use (all method);

2. Increased prevalence of long-term modern method contraceptive use; 3. Decreased adolescent birth rate between the age of 15-19 years (age specific fertility rate/ ASFR). |

a. Decreased total fertility rate (RTF) to 2.3 by 2019 (2012:2.6);

b. Increased prevalence of contraceptive use (CPR) in all methods to 66% by 2019 (2015:60.9%);

c. Increased long-term modern method of contraceptive use to 23.5% by 2019 (2015:22,5%);

d. Decreased number of teen pregnancy between the age of 15-19 years (age specific fertility rate/ ASFR) to 38 by 2019 (2015: 48) |

| 3.8 Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all. | 1. Increased financial protection

2. Increased equalization and quality of healthcare services, as well as resources; 3. Increased financial protection, including catastrophic expenditure for healthcare. |

a. Decreased unmet need healthcare facilities to 1% by 2019 (2015:7%).

b. Increased national Health Insurance coverage (JKN) to 100% by 2019 (2015:60%). |

| 3.9 By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination. | NA | N/A |

| 3.a Strengthen the implementation of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in all countries, as appropriate. | 1. Increased control over communicable and non-communicable diseases and increased environmental health; | a. Prevalence of smokers among population under the age of 18 years to 5.4% by 2019 (2015: 7,2%). |

| 3.b Support the research and development of vaccines and medicines for the communicable and non-communicable diseases that primarily affect developing countries, provide access to affordable essential medicines and vaccines, in accordance with the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health, which affirms the right of developing countries to use to the full the provisions in the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights regarding flexibilities to protect public health, and, in particular, provide access to medicines for all. | 1. Availability of medicines and the quality of medicines and food | a. Increased percentage of medicines and vaccines availability in Puskesmas to 90% by 2019 (2014: 75,5%). |

| 3.c Substantially increase health financing and the recruitment, development, training and retention of the health workforce in developing countries, especially in least developed countries and small island developing States. | 1. Increased equalization and quality of healthcare services, as well as resources. | a. Increased number of Puskesmas equipped with 5 types of health workers to 5600 by 2019 (2013: 1015). |

| 3.d Strengthen the capacity of all countries, in particular developing countries, for early warning, risk reduction and management of national and global health risks. | NA | NA |

Availability & Quality

In terms of primary healthcare, Indonesia has an extensive number of Puskesmas that makes primary healthcare facilities are accessible for 90% of the population, however the availability of health workers and hospital beds remained inadequate.[1] Inequity of available physicians and nurses/midwives are very apparent among rural and urban areas,[2] however there is no data showing the number of health workers at subdistrict level (Kecamatan), the data is important to comprehensively assess the adequacy gaps between geographical areas per 1000 population.[3]

[1] World Bank, Indonesia’s Health Sector Review, 2012, page: 16, available at: http://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/EAP/Indonesia/HSR-Overview-.pdf

[2] World Bank: http://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/EAP/Indonesia/HSR-Overview-.pdf

[3] Each sub-district (Kecamatan) in Indonesia is inhabited between 9,000 to 45,000 population.

Accessibility

As it has mentioned earlier, the availability of Puskesmas as primary health facilities is very limited at villages/kelurahan level, covering only about 12% of villages/kelurahan across the nation. In less dense regions in Indonesia, distance between one village to another may take hours of traveling, and can be expensive, making healthcare facilities less physically and economically accessible for people in rural or remote areas. Therefore it is necessary to have a quality inpatient Puskesmas in every sub-district[1] to facilitate people to access adequate healthcare facilities wherever they are.

This requirement has, actually, been set forth in the Health Ministerial Regulation No. 75/2014 on Puskesmas requiring all subdistrict regions to have at least 1 Puskesmas, however there is still no data showing the number or percentage of Puskesmas at the subdistrict level. Therefore, it is important to include an indicator showing the availability of Puskesmas subdistrict level both for inpatient and outpatient Puskesmas.

[1] A subdistrict in an urban area consists of 5 villages/kelurahan and 10 villages/kelurahan in a rural area. See, Article 6 paragraph (1) of the Government Regulation No. 19/2008.

Vulnerable Groups

People with disabilities may face more challenges in accessing healthcare facilities in comparison to those who are without disabilities. According to WHO, prohibitive cost, particularly with regard to health services and transportation, are the major challenges for disabled people to access health services.[1] Therefore, in order to fulfill the right of disabled people to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health, it is important to ensure that people with disability are covered by health insurance and, for those who are unemployed and poor, to receive premium payment assistance (PBI). Moreover, in terms of physical accessibility, it is very important to provide sufficient number of ambulance in every Puskesmas at subdistrict level.

With regard to health insurance, indigenous people are also among those who may find difficulties in enrolling to the national health insurance program (BPJS). To enroll to BPJS program one is required to have legal identities, such as Family Card (KK) and Identity Card (KTP), while many indigenous people do not have legal identities therefore, it is difficult for them to have a health insurance. In light of this fact, an intervention is necessary to ensure that indigenous people are not left behind in the enjoyment of the right to health.

[1] WHO, Disability and Health Fact Sheet, available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs352/en/

| National Targets | National Indicators | Suggested HRBA Indicators |

| 3.1

– Increased health status of women and children; – Increased access and quality of healthcare for women and reproduction; |

a. Decreased number of maternal mortality to 306 per 100 thousand of childbirths by 2019 (2010: 346);

b. Increased percentage of births delivered in healthcare facilities to 85% by 2019 (2015: 75%); c. Increased percentage of births attended by skilled healthcare personnel to 95% (2015: 91,51%). |

– Percentage of villages with attending skilled health personnel/midwives. |

| 3.4

– Increased control over communicable and non-communicable diseases and increased environmental health; – Increased quality of and access to mental health and drugs rehab facilities. |

a. Decreased percentage of smoking among population ≤18 years of age to 5.4% (2015:7.2%);

b. Decreased prevalence of hypertension to 24.3% by 2019 (2015:25.8 %); c. Non-increase prevalence of obesity among population above 18 years of age to 15.5% by 2019 (2013: 15.4%); d. Percentage of women between the age of 40-50 years to have early detection of cervical and breast cancers; e. Increased number of regencies/municipalities to have community healthcare facilities (Puskesmas) providing mental healthcare services to 280 by 2019 (2014: 50); f. Increased percentage of regional general hospital to provide mental health/psychiatric services to 60% by 2019 (2014: 13.5%); g. Increased proportion of treatment for households with mentally-ill member(s) to 61.8% by 2019 (2014: 38.2%). |

– Proportion of subdistricts with attending mental health professionals. |

| 3.7

– Increased prevalence of contraceptive use (all method); – Increased prevalence of long-term modern method contraceptive use; – Decreased adolescent birth rate between the age of 15-19 years (age specific fertility rate/ ASFR). |

a.Decreased total fertility rate (RTF) to 2.3 by 2019 (2012:2.6);

b.Increased prevalence of contraceptive use (CPR) in all methods to 66% by 2019 (2015:60.9%); c.Increased long-term modern method of contraceptive use to 23.5% by 2019 (2015:22,5%). |

– The availability of a national curriculum on sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) education;

– The number of schools providing/integrating SRHR education (segregated by school levels: SD/SMP/SMU) |

| 3.8

– Increased financial protection – Increased equalization and quality of healthcare services, as well as resources; – Increased financial protection, including catastrophic expenditure for healthcare. |

a. Decreased unmet need healthcare facilities to 1% by 2019 (2015:7%).

b. Increased national Health Insurance coverage (JKN) to 100% by 2019 (2015:60%) |

– Percentage of out-of-pocket health expenditure spent by JKN members;

– Proportion of disabled and/or indigenous people without access to healthcare facilities; – Proportion of indigenous people without health insurance. – Improving programs of mainstream health services based on human rights and non-discriminative principles. |

| 3.9

NA |

N/A | – As the right to health also includes the right to enjoy a good and healthy environment, it is important for the GoI to also adopt the Global Target No. 3.9 and its indicators. |

| 3.c

– Increased equalization and quality of healthcare services, as well as resources. |

a. Increased number of Puskesmas equipped with 5 types of health workers to 5600 by 2019 (2013: 1015). | – Proportion of subdistricts with available Puskesmas providing inpatient services;

– Proportion of Puskesmas with ambulance service at subdistrict level. |

| Data Resources:

– Bureau of Statistics (BPS) – Complains reports from related institutions, namely The Witness and Victim Protection Agency (LPSK), National Commission on Human Rights KOMNAS HAM of Indonesia (Komnas HAM), National Commission on Violence Against Women (Komnas Perempuan), Presidential Staff Office (KSP), Ombudsman, Foundation of the Indonesian Legal Aid Institute (LBH) and civil society organizations working in the health sector. |

||

With regard to the access to health, The World Health Organization (WHO) would be a strong partner for the GoI to improve the full realization of the people’s right to health, both at policy and implementation levels, particularly in the areas of prevention and control of communicable and non-communicable diseases; improvement of child, adolescent and reproductive health; improvement of access to quality health services in support of Universal Health Coverage; and preparedness, surveillance and effective response to disease outbreaks, acute public health emergencies and the effective management of health‐related aspects of humanitarian disasters.

UNFPA would be a strong partner of the GoI contributing to Indonesia’s SDGs agenda particularly to increase availability and use of integrated sexual and reproductive health services, including those related to family planning, maternal health, and HIV, that is gender responsive and meet human rights standards for quality of care and equity in access. Priority is also given to adolescents by promoting availability of comprehensive sexuality education and sexual and reproductive health care.